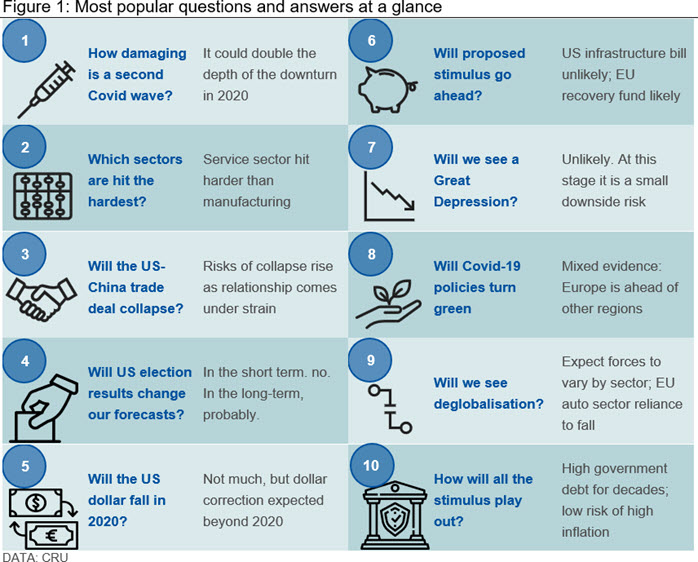

Covid-19 has changed the global landscape dramatically. Here we set out answers to the most popular 10 questions that our customers have been asking.

They range from what might happen in the near-term (the effect of a second Covid-19 wave) to what a post-Covid-19 norm will look like: what are the consequences of the unprecedented Covid-19 stimulus?

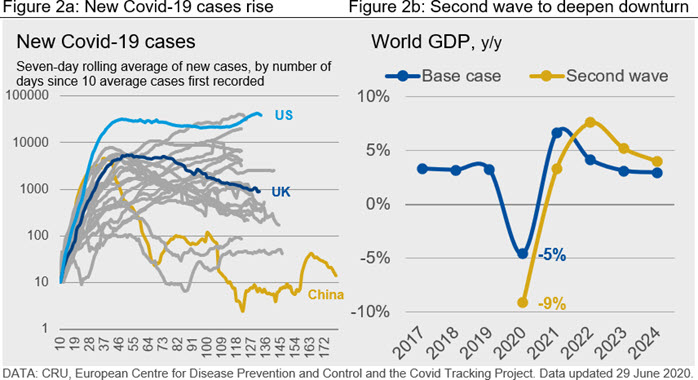

How will a second Covid-19 wave change CRU’s forecast?

A second Covid wave risks deepening the 2020 global downturn.

In our base case forecast, we assume that lockdowns across major economies end in Q but social distancing (enforced or voluntary) continues into Q4. Q2 is expected to be the trough in global activity, followed by a recovery in Q3. Implicit in that forecast is the assumption that there is no sizeable second outbreak. Fears of a second wave have increased following the recent rise in cases in China, Germany, and the USA (Figure 2a). CRU calibrate a scenario in which new outbreaks gives rise to a significant rise in Covid cases, that lead to two additional lockdowns (in Q4 of 2020 and Q1of 2021). The lockdowns are likely to be less stringent than those imposed earlier in the year but would be present in all the major regions. If that did happen it could lower world GDP growth to -9% in 2020, almost twice the size of our June base case forecast of a 5% fall.

Which sectors will be hurt the most by Covid-19?

Hospitality, retail, and transport are hit hardest by Covid-19 (Figure 3).

These sectors will continue to suffer as the need for social distancing will constrain spending at restaurants and in clothing shops. We expect the service sector to be hit harder than the manufacturing sector in this downturn. We also expect winners and losers within manufacturing. For example, motor vehicles will recover only slowly given its weaker footing following rising climate awareness and rising protectionism. In contrast, high tech, and electronic industries, which have prospered recently, are expected to accelerate further as consumers plan for more time at home. In that sense Covid has accentuated existing sectoral trends.

Will the US-China trade deal collapse?

![]()

Risks of the trade deal collapsing are up, as tensions build between the two sides.

Under the US-China phase I trade deal, on 15 January, China agreed to purchase more US goods and services to a combined value of $200 billion over 2020-2021 compared to their 2017 levels. The Peterson Institute tracks China’s monthly purchases of US goods and finds that on a prorated basis, China has fallen behind. This has sparked fears that the phase I deal will collapse. Strictly speaking it is the year-end figures that matter, so China could still meet its target with surging purchases later in 2020. The trade deal aside, accusations on the origin of Covid-19 and China’s proposed new security laws on Hong Kong have led to a deterioration in US-China relations.

Our expectation is that the relationship will deteriorate further, ahead of the election. CRU’s previous trade war scenario analysis showed that additional tariffs on all Chinese imports would lower growth in China and the USA. Taken together, world GDP could fall by a further 1 percentage point. Some have argued that a tough stance on China may benefit Trump’s chances of re-election, but it would be an unwelcome development for the global economy.

Will US presidential election result change our forecasts?

New policies, not a new president, would alter our forecasts. We do not expect US macro-economic policies to change in November; but climate policy may change under Biden. Elections are hard to call. Today Biden is the most likely winner, according to presidential approval ratings, and a free to access model by the Economist magazine.

Media reports suggest that Trump’s current poll ratings are low because of the uptick in Covid-19 cases and the high rate of unemployment in the USA. That said, in the past, most incumbents get re-elected for a second term, which favours President Trump. It is too early to say who will win the election in November, as that will depend on how Covid and the economy evolves.

We do not expect US macro policies to change much in November. The Fed is independent, so the monetary stance will not change. The fiscal stance will also not change, as Congress will do what is needed to secure a recovery from the Covid crisis. On trade policy, Biden is expected to maintain a tough stance against China (see Brookings). A Biden victory would recommit the USA to the Paris Agreement, altering the long-term outlook for the mining industry.

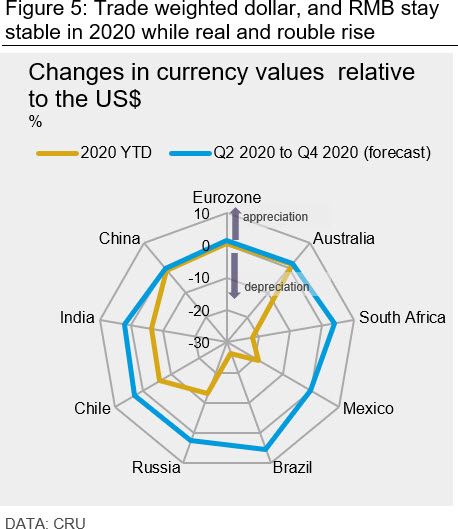

How will the US dollar move this year?

We forecast the trade weighted dollar to remain stable for the rest of 2020.

So far in 2020, most currencies have lost some ground against the dollar (yellow line). CRU estimates that the broad trade weighted dollar is still overvalued. We judge that pandemic uncertainty has supported the dollar in 2020, given its role as a ‘safe-haven’ currency. The expected stability of the dollar for the rest of 2020 hides differences in bilateral currency movements: the RMB will be stable; and the real and rouble will gain 5% and 3% respectively against the dollar. Beyond 2024 we expect the trade weighted dollar to fall significantly, as pandemic uncertainty fades and fundamental factors reassert themselves.

Will the US infrastructure bill and EU recovery fund pass?

The US bill is unlikely to be passed this year; the EU fund is likely to gain approval.

Covid-19 and the recession that has hit the USA have led many to call for additional stimulus beyond the CARES Act ($2.5 trillion) and the Paycheck Protection Program ($483 billion). A bipartisan infrastructure plan, exceeding $1 trillion, would be welcome at a time when the US economy is suffering from double digit unemployment rates. However, the Democrats and Republicans have long disagreed on how to finance and structure this “multibillion infrastructure plan”. Our view is that the chances of a US infrastructure bill being agreed before the election is low in view of the political deadlock and current pressure on State budgets. Such a bill would be an upside risk to our outlook.

Next Generation EU is the EUR750 billion recovery package announced by the European Commission on 27 May. It aims to revive the economy and simultaneously help countries most affected by Covid-19. The plan is for funds to be raised on capital markets and then distributed to member states, based on strict criteria, such as investment to raise long-term productivity. The package is yet to be agreed by member states, but our view is that it will probably be passed later this year.

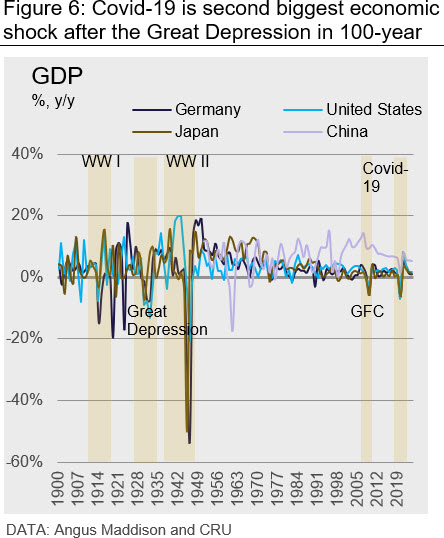

Will the global economy enter a depression?

Depression is unlikely; it is a downside risk.

Covid-19 has led to a global downturn that is larger than the global financial crisis (GFC). That has led many to worry that growth could fall to the lows seen during the 1930s Great Depression. Our base case forecast assumes that growth will resume in 2021. We judge a global depression to be a downside risk, since policymakers should have learnt from the mistakes they made in the 1930s – which relate to their understanding of the economy and policy inaction (e.g. Romer). We do not see that today. Instead we see policy action on an unprecedented scale. Major central banks have reiterated their commitment to do “whatever we can and for as long as it takes” to return the economy to stable employment and inflation.

Will Covid-19 policies turn green?

So far this is happening only at the margin and mainly in Europe.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues had risen to the top of the agenda prior to Covid. The spotlight has now shifted to Covid. Many have argued that Covid stimulus policies should be skewed to benefit the environment too. Some of this is happening (e.g. the EU and China have in 2020 stepped up their subsidies for electric vehicles). In addition, the new EU recovery fund proposes to allocate more funds to countries that are furthest from the transition to a climate-neutral economy. However, not all developments have been climate friendly. For example, China has been approving new coal plant power capacity at the fastest rate since 2015. That is a sign that at times meeting both goals can be very difficult.

Will we see deglobalisation, and a break in supply chains?

CRU expects the direction of globalisation to vary by region and sector.

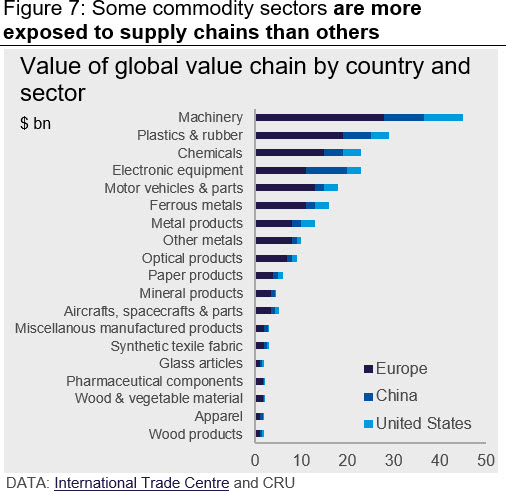

There is a lot of speculation about what the new normal will look like after Covid. At this stage, some predict deglobalisation; some greater regionalization; and others expect supply chains to become more diversified. Our view is that changes to supply chains occur all the time, particularly during crises. Covid will be no different. However, it is too early to predict how these will evolve. Figure 7 shows that value of global supply chains varies by sector; dependence is greatest in the EU.

Motor vehicles and parts production currently rely heavily on Europe. That dependency is likely to fall in the next decade as strategic and protectionist forces rise. Other sectors, e.g. electronics, are likely to see an increase in globalisation.

What are the long-term consequences of Covid-19 stimulus?

We will see higher levels of debt for a long time, but the risk of high inflation remains low.

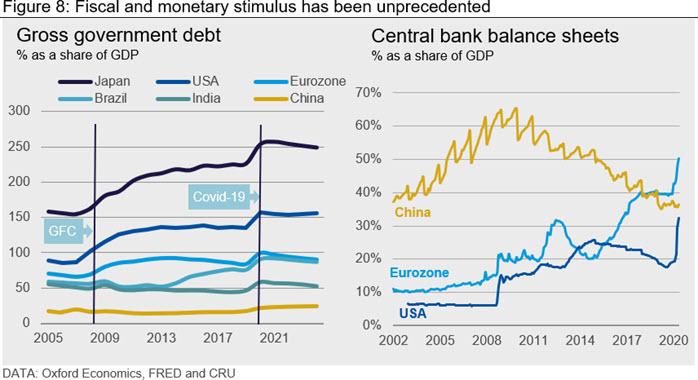

Covid-19 is an unprecedented shock to the economy which has been matched by unprecedented policy support. There are concerns about how this stimulus will cascade through the economy and whether it will lead to undesirable consequences such as high debt and high inflation. Our view is that government debt levels will indeed take a step up, and remain elevated for a decade to come, just as it did after the GFC. High debt on its own is not a bad thing. Many argue that low interest rates reduce the cost of high government debt, which means the economy can service and maintain a higher level of debt than in the past (e.g. see Blanchard). If the fiscal spending is successful in returning the economy to pre-Covid-19 levels of growth then debt levels will fall, slowly but surely. That is our base case forecast. The risk to this outlook is that growth returns more slowly, in which case the debt dynamics would be adverse, resulting in rising not falling debt.

Interest rates in major economies were low when Covid-19 arrived, meaning that for many central banks QE was the only game in town. Figure 8 shows that QE has been used extensively by major economies, leading the central bank balance sheet to rise. A debate continues, on whether QE on this scale, and for an extended period, equates to monetary financing which in the past has led to high rates of inflation. Our view is that inflation is not a worry in the medium term (confirmed by the June FOMC and ECB projections). At this stage we do not think it is a material worry in the longer-term either, since we are facing the largest global contraction since the Great Depression. Our view is that the priority for policy makers is to address the health crisis and do whatever is needed to return the economy to its pre-Covid-19 growth rates.

Explore this topic with CRUEconomics