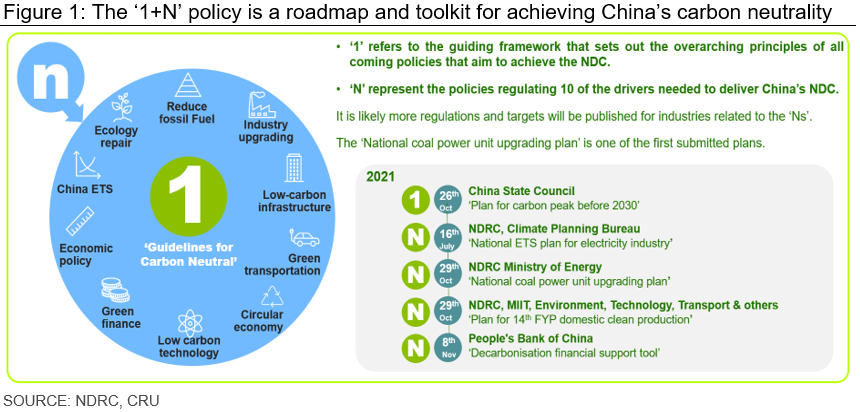

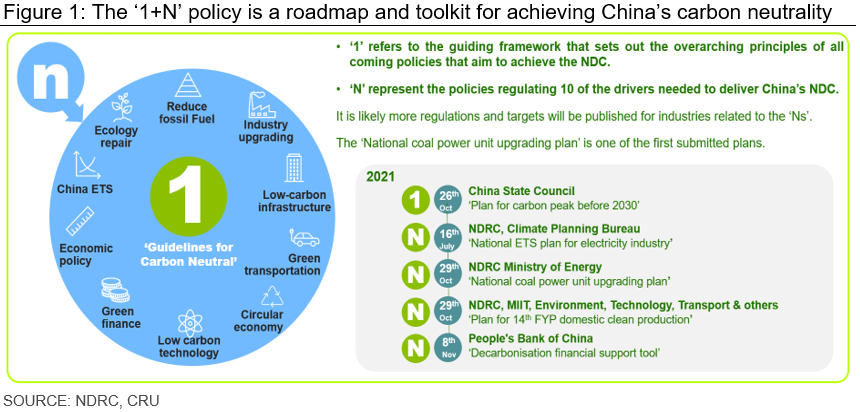

The most noteworthy development was the release of two policy documents: the Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy (the ‘Working Guidance’) and the Action Plan for Reaching Carbon Dioxide Peak Before 2030 (the ‘Action Plan’). These represent the basis of China’s ‘1+N’ framework for reaching its carbon targets of peak carbon by 2030 and net-zero by 2060.

While the Working Guidance acts as the foundational pillar for China’s overall carbon emissions strategy (representing the ‘1’ of the ‘1+N’ framework), the Action Plan is the first in a series of more granular and applicable policy documents (representing the first of the ‘N’ documents). We expect more such policy documents and guidelines to be released targeting specific areas of industry in 2022 (Figure 1).

This Insight focuses on the implications of recent policy for the industrial sector, looking at the 14th Five-Year Plan on Industrial Green Development (the ‘Green Development’).

14th Five-Year Plan On Industrial Green Development

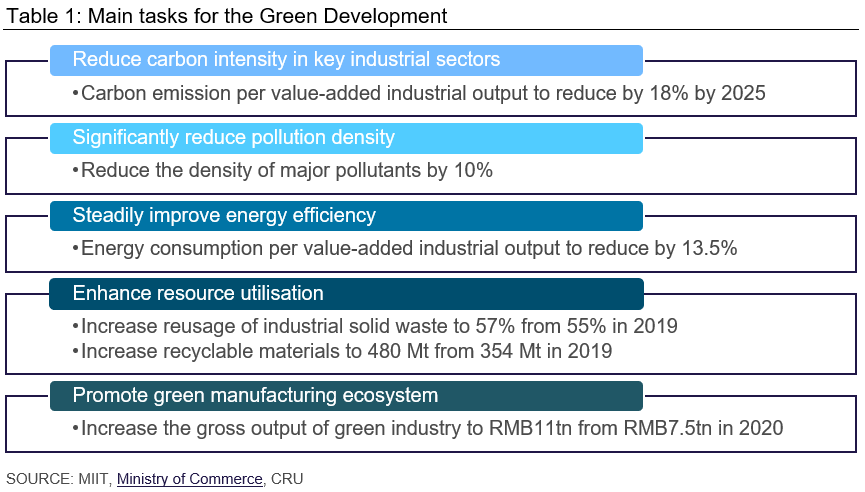

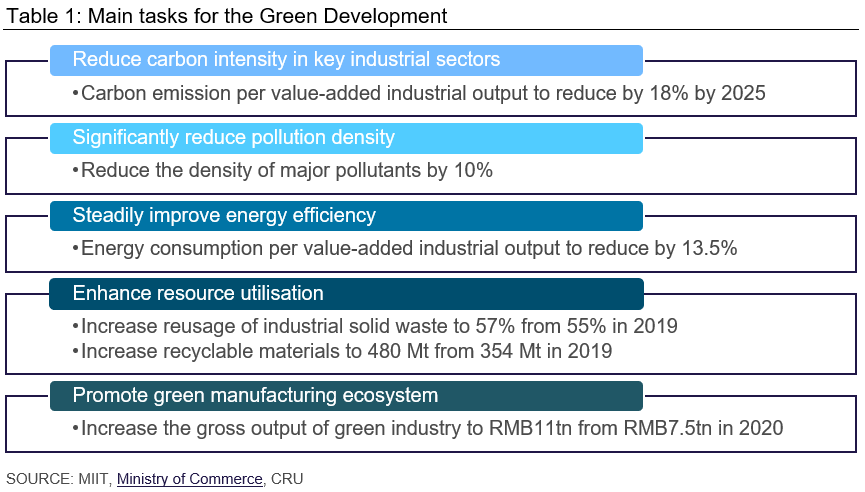

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) released the Green Development in December 2021. The plan examines the current status, the basic principles, and main objectives of green development in China. The plan also details use of green and low-carbon technology and equipment, increased efficiency of energy resources, progress in the reduction of carbon emissions, and the reduction of CO2 emissions per unit of industrial added value by 18% (Table 1).

Some market participants expected China would take drastic measures to cut carbon emissions in 2022, but recent events and actions indicate that the Chinese authorities will not be taking an extremely restrictive approach and may even ease some of the more stringent environmental regulations of 2021. In June 2021, the NDRC warned against ‘campaign-style’ carbon reduction measures – that is, doing too much too quickly, resulting in unsustainable measures that could potentially damage supply chains and the business environment. The Chinese government will seek a more ‘orderly’ means of tackling carbon emissions, while staying clear of bottom-line economic stability and recovery. The problems for the energy and industrial sectors* in 2021 Q4 caused by the Dual Control policy are an indication of the costs of moving too fast.

*Note: CRU subscriber only content. Not a subscriber? Learn more

China will adopt stringent but flexible, targeted measures for its green transition

Energy constraints for China’s industry will be tighter in the next five years. While painful, this will be an important driver for China’s green development. Industries facilitating the Chinese green transition will benefit from these policies. In addition, energy intensive industries will become less vulnerable to energy consumption control and volatility in energy prices, as they become more efficient and less carbon intensive.

Energy consumption control of the industrial sector is the key to China’s road to net zero. Two-thirds of total energy consumption comes from the industrial sector, and China will continue to set clear goals on energy consumption control and carbon intensity control for the industrial sector – as it has done so in the past decade.

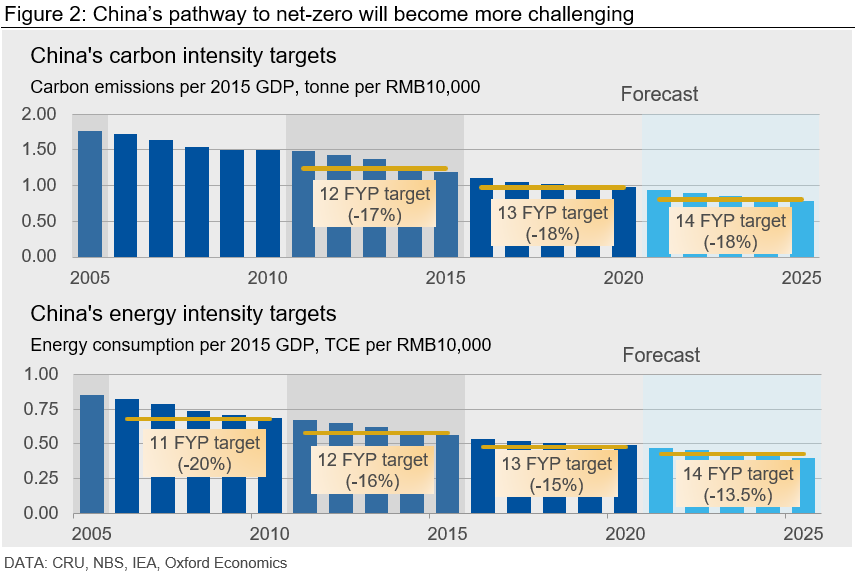

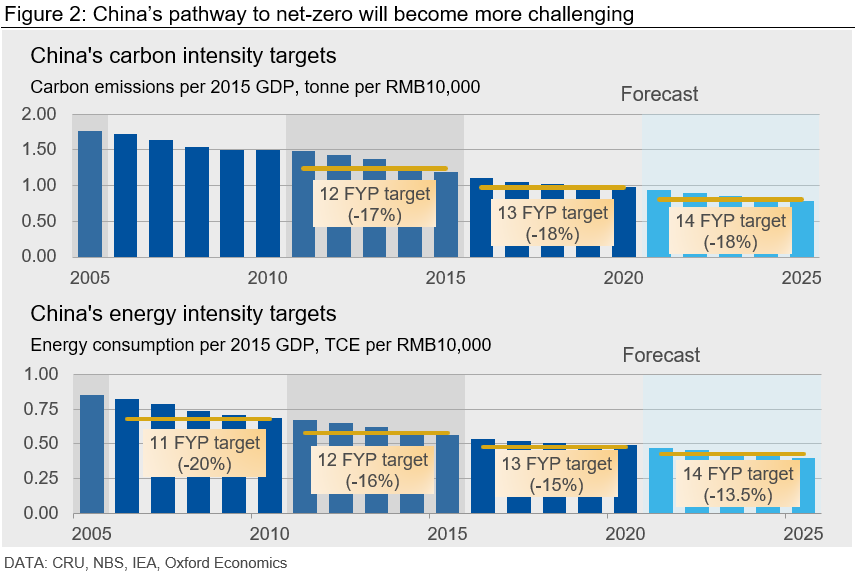

In the Green Development, the industrial sectors are requested to reduce energy intensity by 13.5% and reduce carbon intensity by 18% (Figure 2). Though these numbers are close to the ones set for previous FYPs, the industry will start to experience diminishing marginal returns in the following years. For example, better energy recovery and improvement of the production process have helped the steel industry achieve the energy intensity goal in the 13th FYP period. To continue the same pace of energy/carbon reduction, the steel industry will need to switch toward electric arc furnaces (EAF) from the current blast furnace/basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) process. This will require higher investment and mean higher raw material costs. It will also require changes in other parts of the value chain, for example higher recycling rates – see the section on green development below.

China will prioritise energy intensity controls over an energy consumption cap

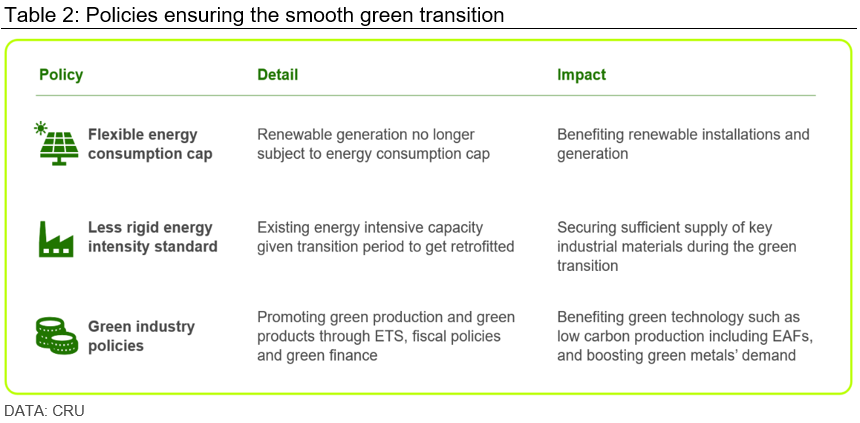

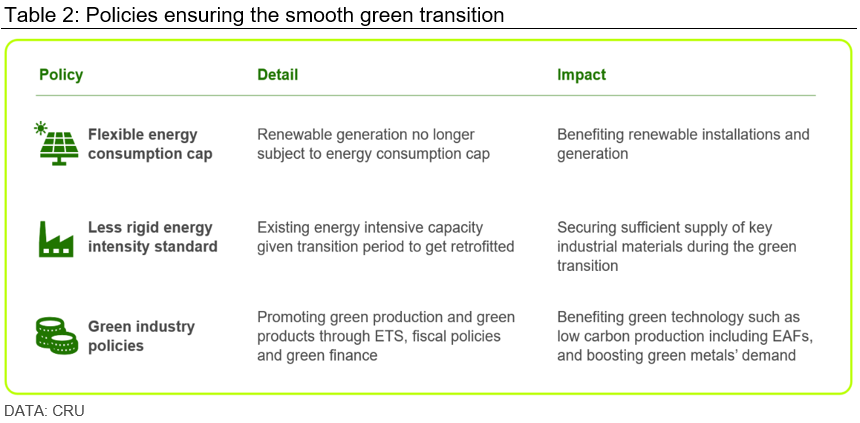

Despite attaching great importance to the 2030 carbon peak commitment, China does not set any restrictive goals for total energy consumption or total carbon emission for 2025 in the 14th FYP. This allows the economy to balance its dual goals of development and green transition more easily. In fact, several policies have been announced to assist a smooth transition to a greener state. This can ease the pressure on energy intensive industries in the next five years (Table 2).

China will set clearer and more realistic national energy intensity targets, and make sure these are being achieved through assigning them to provinces. The energy targets will exist alongside other local goals such as economic development and people’s wellbeing. For example, Sichuan province released its carbon neutral roadmap in December, drafting its green transition path to achieve its energy consumption target – considering its energy resources and industrial mix. Next, the progress of the targets will be reviewed annually to ensure the provinces are on track. This will then make sure the national intensity targets are achieved.

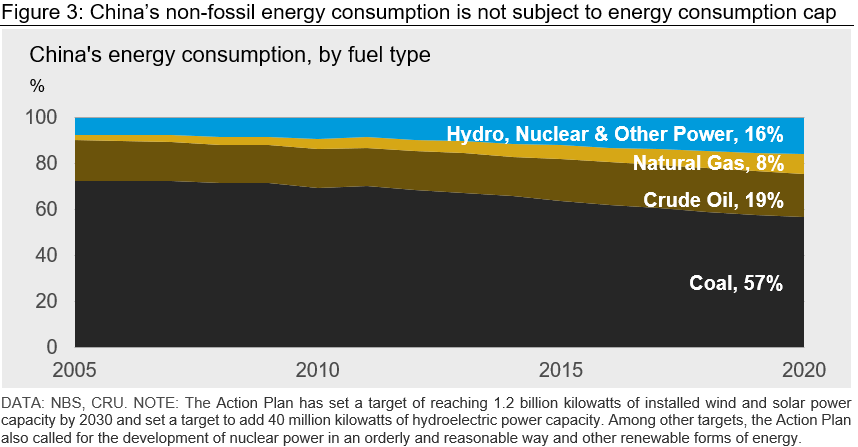

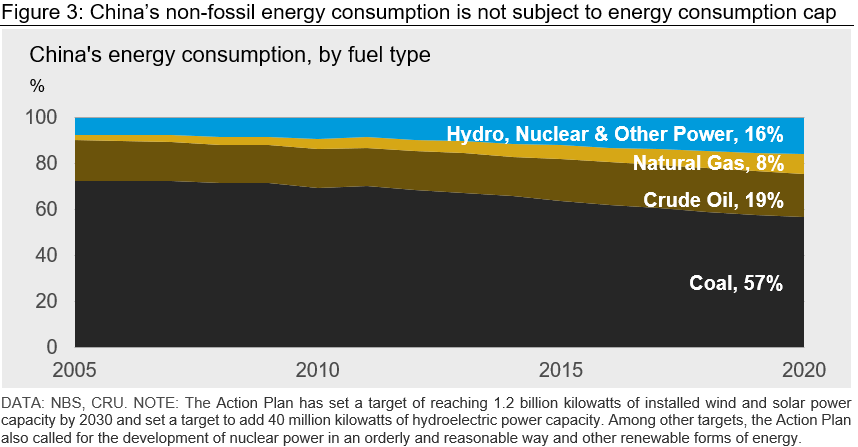

Yet, China’s energy consumption cap is more flexible, trying to decouple the energy consumption and carbon emission controls. In the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2021, China announced that renewable generation, as well as non-fossil energy consumption, are not subject to energy consumption cap (Figure 3). This means the restriction of carbon emissions will not necessarily lead to restrictions on energy consumption. This eases the pressure of energy constraint for the economy without hindering its green transition. It will also create incentives for investment in renewable generation capacity, especially for provinces with tight energy consumption ‘budgets’, abundant natural potential for renewable power, and urgent needs for economic growth.

Energy-intensive industries will face higher energy costs

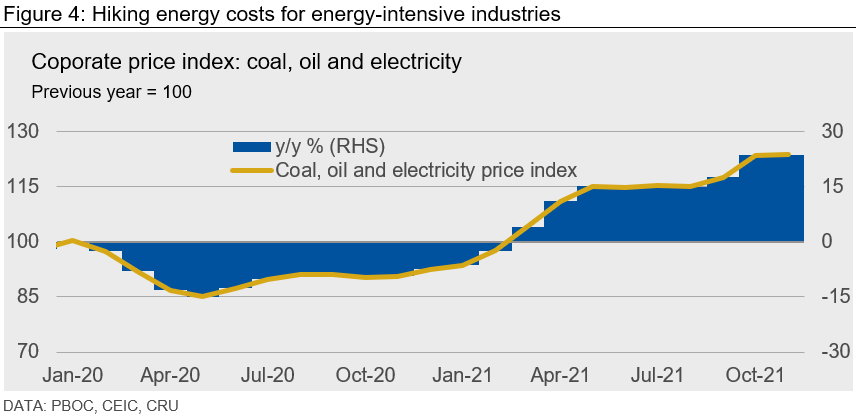

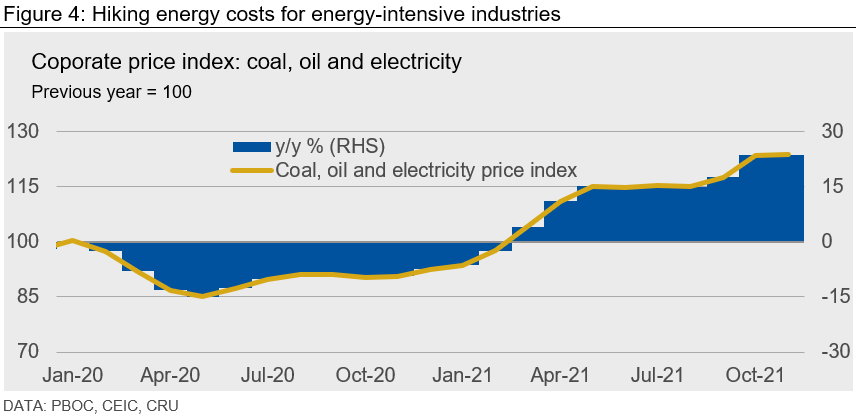

Energy-intensive industries, including steel, non-ferrous metals, and cement, will be more vulnerable to higher power tariffs in the next five years (Figure 4), as from 2020, they can no longer get a power tariff discount, which could hit profitability.

The new energy efficiency standards released from NDRC, state that new capacity in energy intensive industries must achieve advanced efficiency levels to get approval; while existing capacity has been given a three-year transition period to get retrofitted. This means that the policy set-up is less rigid, and more efficient plants in the energy intensive industry will suffer less in the medium term.

Green development of the industry will be encouraged

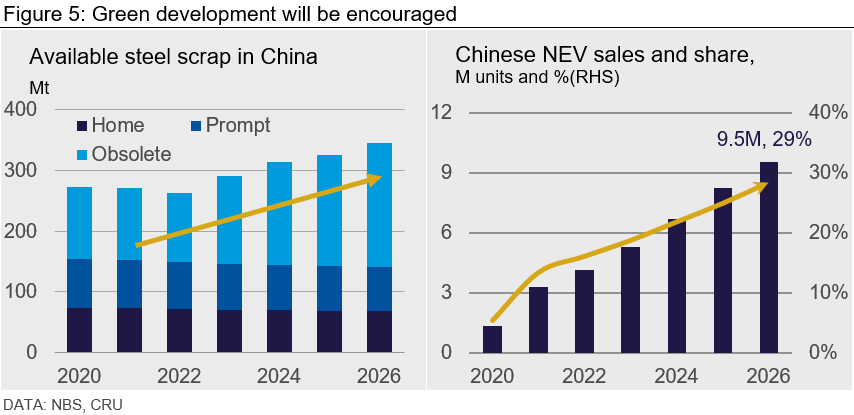

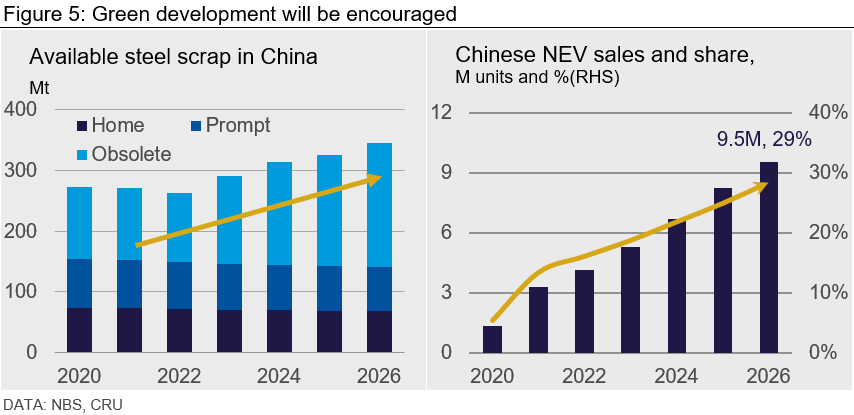

Several policies have been set for the Green Development of industry in the next five years. This includes increasing recycling rates, cleaner production in high polluting industries, and promotion of green products. For example, China set a target of increasing scrap steel usage by 23% and increasing scrap non-ferrous metal usage by 11% by 2025 compared with 2020 levels. In addition, cleaner production of oven coke and ironmaking process will be promoted, 50% of steel capacity and 90% of coking capacity is expected to hit the ultra-low emission target by 2025. Moreover, green products, including new energy vehicles (NEVs), energy saving home appliances, bioproducts, and high efficiency new energy equipment will increase in market share (Figure 5).

Green finance is the key to achieving carbon neutrality

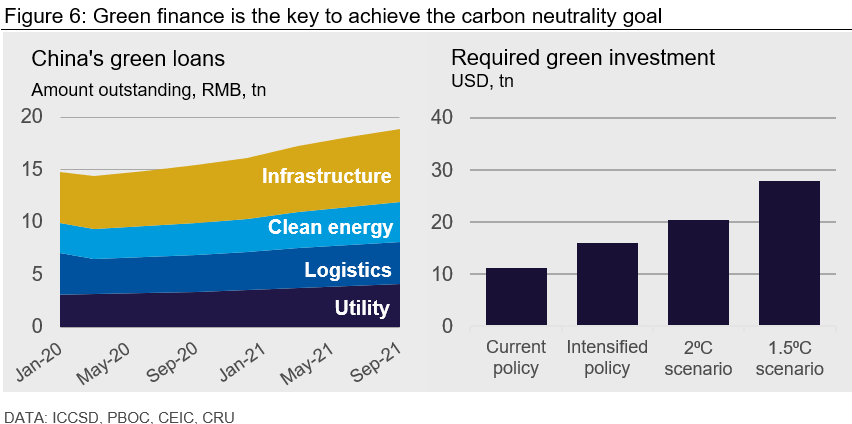

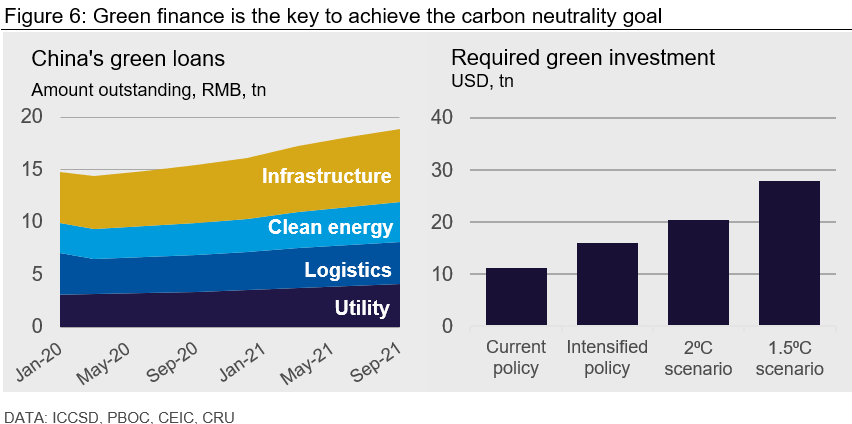

Achieving China’s carbon goals will be expensive. Institute of Climate Change and Sustainability Development at Tsinghua University estimated that almost RMB140 tn (~US$27.8 tn) is needed over the next 30 years to achieve the 1.5°C goal. The government’s strategy is to actively promote green finance – a set of policies and incentives to channel private sector capital, primarily through loans and bonds, into green projects and industries.

The government is adopting different tools for green finance, including making it more attractive to banks. For example, in November, PBoC launched its carbon-reduction support tool, designed to provide cheap funding to financial institutions that operate nationwide to channel low-cost loans to businesses in the clean energy, environmental protection, energy conservation, and carbon-reduction technology industries (Figure 6).

In addition, the government is considering ‘green credit’ and ‘green trade’. The PBoC is considering green credit and green bond performance in bank assessments. The commerce ministry recently released the five-year plan for promoting foreign trade, which proposed to set up a “green trade index” and collect data on the carbon intensity of trade.

China is also looking to align green finance standards with international best practices. With an eye on cross-border investment, China and the EU have finally formulated jointly recognised standards for defining green projects in November (which is open for public feedback until January 2022), in a move to help channel global capital to sustainable businesses in the two markets.

In conclusion, we expect that the energy-intensive industries will see higher energy costs and more unfavourable policies to facilitate the nation’s green transition. However, the policies also set out a meticulous plan to smooth the transition without repeating the power shortage event in September 2021. Regardless of how ambitious China’s carbon emissions plans are, or how urgent the international cries for action are, China’s authorities will not allow people to go without power or heating, which will necessarily require the continued burning of fossil fuels until all demand can be met by alternative sources.

Explore this topic with CRU