Contributor Victor Rodriguez

Head of Consulting, EMEIA View profile

As the third largest economy in Latin America, what happens next in Argentina has consequences for Brazil, its largest trading partner and, perhaps, the political landscape across the region which is already fraught with a good deal of uncertainty.

Too much pain and not enough gain

November 2015, an indication that he was not the clear first choice for the majority of voters. However, to those outside Argentina, particularly the financial markets, his election was interpreted as the country wanting to break with the prior, economically damaging Nestor Kirchner/Cristina Fernandez administration which extended back to 2003.

The first year of the Macri administration was prolific. The peso was liberalized to a more realistic level. Import licenses and taxes on exports were eliminated. Financial markets gained enough confidence that Macri would not allow a default to occur and in April 2016 Argentina issued its first bonds via international capital markets in 15 years. The government began to release statistics which reflected the country’s economic reality and the rest of the world began to breathe a sigh of relief that this key economy might progress further.

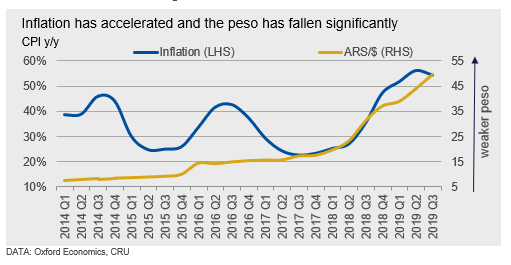

In addition to these measures—which were clearly aimed at the world outside Argentina— Macri embarked on a moderate austerity plan to reduce government spending and, by extension, inflation. “Gradualism” became the trademark of the first two years of his administration. However, large fiscal deficits were financed by external borrowing, increasing the country’s vulnerability to external shocks. In December 2017, the Government exerted significant pressure on the central bank to reduce policy interest rates, despite an acceleration in inflation, which caused the peso to depreciate even further and allowed another round of inflation to begin.

When it became clear in Q2 2018 that the global economy was beginning to lose momentum, the broad sell-off in emerging markets resulted in much higher funding costs, prompting Macri to approach the IMF for a loan to manage Argentina’s external funding needs. Although the deal with the IMF was heralded outside Argentina as a smart move, it was deeply unpopular among Argentines who blame the IMF for the severe economic crisis back in 2001. In hindsight, the appeal to the IMF might have marked the beginning of the end of Macri’s presidency.

An “Argentina for all” with challenges ahead

Argentina’s electoral system grants first-round victory to the candidate that surpasses 45% of the votes and Alberto Fernandez defeated Mauricio Macri, receiving more than 48% of the vote versus Macri’s 40%. This is the first elected office Alberto Fernandez has ever held and his victory is likely the result of the persistent popularity of his running mate, Cristina Fernandez. President-elect Fernandez is perceived as more moderate in terms of economic policy than Cristina Fernandez, but, so far, he has not put forth any clear plan for reversing the country’s economic woes. Instead, he has made general remarks about putting the country “back to production”.

Just before August’s mandatory primary election, when the Fernandez-Fernandez ticket won a landslide victory, the peso was trading at around 45/$. As we write on 28 October, the peso has weakened to 59/$, a decline of more than 30%, which is a good indicator of financial market sentiment towards Argentina right now. Capital controls that were lifted during the first weeks of the Macri administration had to be re-instated at a very high political cost. The Brazilian real has also lost around 5% of its value since Argentina’s primary elections, partially on the prospect of a return to populism in its neighbour. With Venezuela already in dire straits, Ecuador boiling over and even Peru and even Chile now at risk of difficult times ahead, the election result in Argentina takes on even greater political and economic significance.

The election indicates that Argentines are unhappy with the austerity that is going to be necessary in order to put the economy on a stronger growth path for the future. President Macri certainly did not find the right formula or perhaps he never had the underlying support which would have allowed him to inflict some economic pain but show that the longer-term gains to the economy would be worth it.

Whether President Alberto Fernandez will be able to deliver that balance is far from evident. Although he served as Chief of Staff during Nestor Kirchner’s presidency (2003-2007), which ran a fiscal surplus between 2004 and 2007, the world economy is in a much different place today. In 2004, China was still expanding rapidly and a commodity boom was beginning to develop—soy, Argentina’s main export product, was at record highs. Today, China’s growth is being managed so that it slows for the foreseeable future, while growth in the US and Europe will be weaker in 2020.

In January 2018, President Macri spoke at Davos about the extent of Argentina’s economic potential, citing its considerable natural resources and food production potential. The question that needs to be answered now is whether Argentina will remain outward-looking in terms of its economic opportunities or whether it will turn inward, once again.

Explore this Topic with CRU

Contributor Victor Rodriguez

Head of Consulting, EMEIA View profileThe Latest from CRU

Decarbonisation will reshape global steel trade flow

CRU’s Steel Long Term Market Outlook presents comprehensive analysis of global steel trade flows until 2050. Decarbonisation will play a significant role in redefining...